Introduction:

There are around 42,300 new bowel cancer cases in the UK every year, that’s more than 110 every day. Bowel cancer is the 4th most common cancer in the UK, accounting for 11% of all new cancer cases. It is also the 2nd most common cause of cancer death in the UK, accounting for 10% of all cancer deaths

One of the reasons behind these data is that it is often diagnosed when it has already spread or, if it has been diagnosed early, results in metastases in 50% of patients despite treatment.

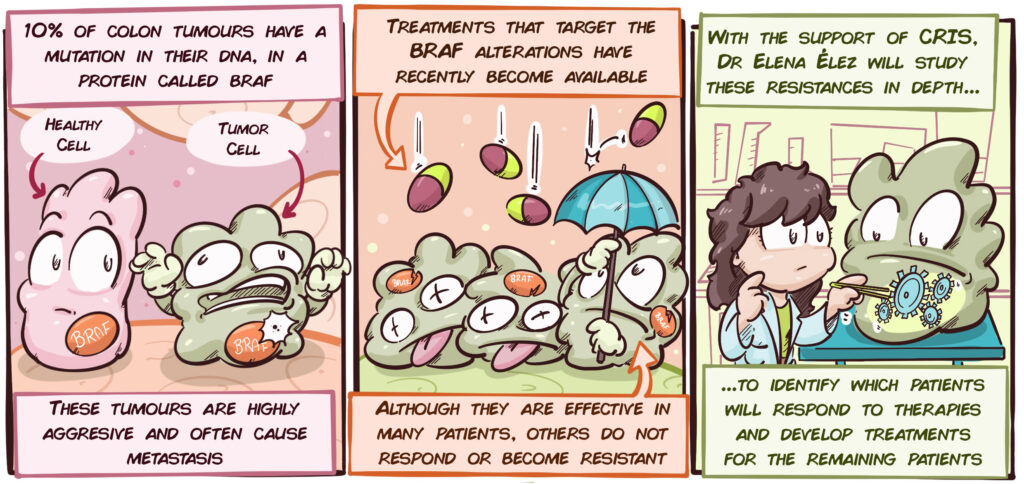

Not all colon tumours are the same. There is a very aggressive subtype that makes up approximately 10% of cases, which is characterized by the tumour cells having a particular mutation in their DNA, in the BRAF gene. Until recently, there was no specific treatment for these tumours. The only possible treatment was chemotherapy-based, which was often unsuccessful at controlling the disease.

Through recent advances in research, it has been possible to develop treatments that attack BRAF and the mechanisms that are altered by this mutation. These treatments therefore have significant potential in colon cancer patients with BRAF mutations. However, although the results are promising, these treatments are not effective on all patients and some of those who respond do so only in the short-term.

Consequently, it is essential that the following aspects are understood in greater depth:

- It is essential to find strategies to identify which patients will respond to treatments that are targeted at BRAF mutations.

- We need to better understand these tumours in order to understand the mechanisms that cause them to stop responding to treatments targeted at BRAF mutations.

- We must identify new treatments for those patients that are resistant to treatments targeted at BRAF mutations.

Only then, will we be able to definitively defeat these highly aggressive forms of colon cancer.

Description of the Project:

Dr Élez’s group is developing an ambitious project in order to address the principal challenges of metastatic colon cancer with BRAF mutations. Its three main objectives are as follows:

Analysis of the tumour tissue structure as a mechanism of resistance:

One of the group’s hypotheses is that tumours that become resistant to targeted therapies have a very different structure from other tumours due to their large mucinous tissue component. In this part of the project, tumour samples from patients with BRAF mutations will be studied and compared with those from tumours that are sensitive and resistant to targeted therapies.

Research into new mechanisms of resistance:

In addition to studying tumour tissue, an in-depth analysis of the DNA and other tumour cell components will be carried out, in order to try to understand how the tumour cells become resistant to the therapies. This can give significant clues about the weak points in these tumours that can be targeted by specific treatments.

One of the strategies that the group will adopt to achieve this is to create animal models with the tumours of the various patients. These models will be used to study the tumours in a biological environment that closely resembles real-life and will enable the efficacy of new treatments to be tested.

Validation of biomarkers:

Dr Élez’s team has identified a characteristic of resistant tumours (called biomarkers) that could be used to predict which patients will and will not respond. It has found that patients whose tumours contain more cells with mutated BRAF may respond better to therapies. In this part of the project, they will study this concept in greater depth and attempt to demonstate that this characteristic could be used in hospitals to distinguish which patients will respond better to the BRAF targeted therapies.

To conclude, this study could provide new clinical tools for the improved diagnosis and treatment of one of the most aggressive forms of colon cancer.