Background:

In the UK, about 1 in 8 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime. Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men. More than 47,500 men are diagnosed with prostate cancer every year – that’s 129 men every day. Every 45 minutes one man dies from prostate cancer – that’s more than 11,500 men every year.

We don’t know exactly what causes prostate cancer but there are some things that may mean you are more likely to get it – these are called risk factors. It is usually detected in the early stages before it spreads and metastasizes and, as a result, is cured in most cases. However, in some patients (5% -10%), these tumours are detected when some metastasis is already present, which complicates the prognosis.

Although a significant percentage of prostate tumours have a good prognosis and can often be cured (largely due to early detection), castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer is an extremely heterogeneous cancer with an often poor prognosis and a life expectancy of less than two years.

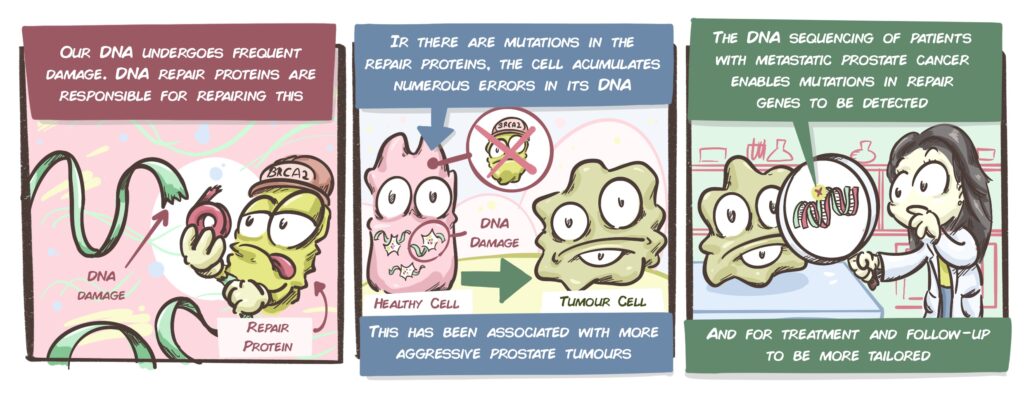

It has been discovered that 30% of patients have DNA repair gene mutations. These genes are essential: during the life of a cell or when it multiplies, there is often little damage to the DNA chains. Normally, there are a series of proteins responsible for detecting and repairing such damage and the cell can continue its life as normal. However, if there are problems in the genes responsible for repairing DNA, the damage accumulates and can cause the cell to change its behaviour. It can transform into a tumour cell and, if this has already occurred, may be more likely to be more aggressive, metastatic or resistant to treatment. Some of the key genes responsible for repair are BRCA1, BRCA2 and ATM. The CRIS Unit for Prostate Cancer has been working for many years on these types of genetic changes in terms of their mechanisms of repair, their impact on the development of tumours and the treatment of patients with them. The Unit’s work and collaborations have contributed to the recent international revolution in metastatic prostate cancer treatments.

These changes/mutations do not usually occur spontaneously in tumour cells but are present in every cell of the body and are inherited from the patient’s parents. This means that several members of a family may carry these mutations, which means that they are susceptible to developing aggressive forms of various cancer types. This is something that this Unit has previously demonstrated (more information here). These inherited mutations are known as germline mutations.

For several reasons, it is important to find these mutations in DNA repair genes as early as possible in prostate cancer patients. Firstly, if they are detected early, more intensive monitoring and patient follow-up can be undertaken. Secondly, specific therapeutic strategies are being developed that work more effectively on patients with these mutations. Lastly, it is important to detect patients with these mutations in order to contact their families and advise them appropriately as they could be at an increased risk of developing certain types of cancer in the future.

Description of the Project:

This project focuses on the importance of sequencing the DNA of patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Although sequencing would make it possible to identify patients at higher risk, monitor them and give them more appropriate treatments when they deteriorate, as well as provide genetic counselling to the family, it is not currently common practice in hospitals. An example of the importance of sequencing can be seen in the results of the PROfound study, which the Unit participated in (more information here). However, this practice only appears in the recommendations of 15 countries and is only undertaken on a fairly regular basis in the US.

This project is part of this context. In the Unit’s previous work, it was clear that patients with mutations in the BRCA2 gene have a poorer prognosis. In a recent study, the Unit demonstrated that metastatic prostate cancer patients with BRCA2 mutations responded better to the order of a routine treatment being changed: rather than administering chemotherapy first followed hormonal treatment, it appears to be more beneficial to administer the sequence in reverse, first the hormonal treatment and then the chemotherapy.

However, for a study to carry enough weight to change routine clinical practice, it needs a larger patient group: in this case, a study that includes at least 2000 patients is needed. As a result, in order to reach 2000 patients, patients from Malaga, but also from other Spanish and international hospitals, will be sequenced. These patients will be included in a study in which several aspects will be studied:

- Confirm that treatment with hormonal treatment followed by chemotherapy is more beneficial than the reverse in patients with BRCA2 mutations.

- Clearly confirm whether mutations in DNA repair genes (in general) take less time to develop resistance to routine treatments than in patients without these mutations.

This project is highly significant as it has the potential to change clinical practice and improve the treatment of patients with metastatic prostate cancer. It could also be key to establishing sequencing as standard practice in these patients.

Furthermore, this study will sequence a huge number of prostate cancer patients with metastases throughout Spain. This is important because, as it is not yet within the recommendations, these patients will receive a procedure that their hospitals cannot yet provide: sequencing, genetic study, closer follow-up and more tailored therapeutic options based on the changes detected.

Latest developments:

Although the pandemic has hit the research hard by complicating the collection of patient samples and making international collaboration difficult, Dr Castro’s team has made significant progress.

To date, it has managed to collect samples from over 300 patients, both from Spanish hospitals and international institutions (Hospital Gustave Roussy in Paris, Istituto Scientifico Romagnolo in Italy and the John Hopkins Medicine School in the USA). These samples have already been sequenced and it is expected that the number of samples analyzed will be increased over the next few months.

One of the great strengths of this research group is that its findings have great potential to change clinical practice and improve how doctors are able to proceed when faced with certain characteristics and situations in their patients. The following is a recent example of this: current medical guidelines associate the appearance and morphology of certain prostate tumours under the microscope with certain genetic mutations. However, in a study of over 170 patients, Dr Castro’s team has demonstrated that this association is inexact. These results, published in the European Journal of Cancer, will help improve the diagnosis of prostate cancer patients.

As previously indicated, prostate cancer patients may have inherited DNA changes from their parents. In order to advise these patients and monitor and evaluate the risks (through Genetic Counselling), Dr Castro’s team has opened a Cancer Genetics Unit. In recent months, 45 males with prostate cancer have been supported; those with inherited mutations have been able to join prevention and early-detection programmes and potential tumours have been detected in their families, enabling them to act as early as possible. This can help to save countless lives.